Intermediate means a substance that is manufactured for and consumed in or used for chemical processing in order to be transformed into another substance […].

Intermediates are exempted from authorisation under REACH Art. 2(1c) and Art. 2(8b)

1 Background

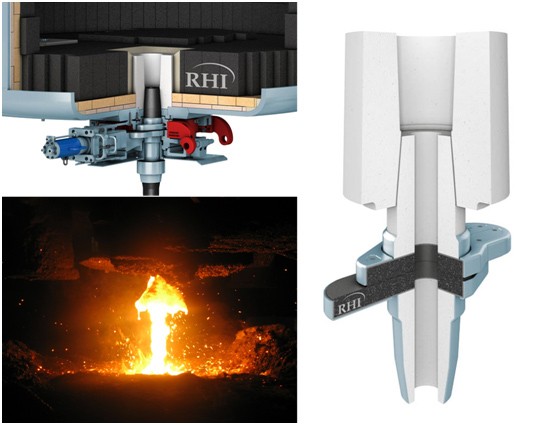

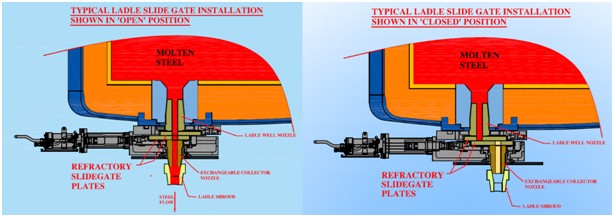

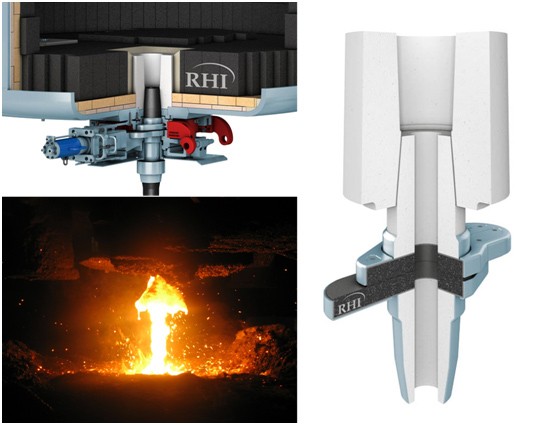

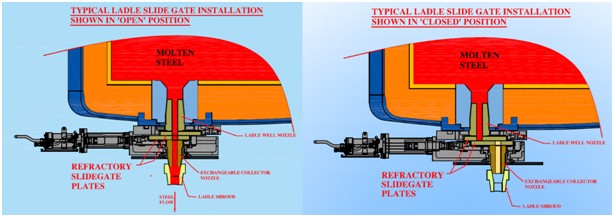

During the manufacture of slide gate assemblies, PRE member companies use “Coal Tar Pitch high temperature” (CTPht) (CAS 65996-93-2) to produce “Coke (coal tar) high-temperature pitch” (CAS 140203-12-9), in the following named “Pitch coke”. A slide gate system is one of the flow control components in the steel casting process. The basic function of the slide gate system is to control the flow of the liquid steel from the ladle to the tundish and from the tundish to the mould (it can also be used for furnace gates). The basic principle of a slide gate system is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. For successful operation, a slide gate system requires different refractory components (assemblies). The slide gate plate for example is one of the most critical refractory components in a slide gate system for liquid steel casting and metering.

Figure 1: Figures showing construction of a slide gate system (top left) position of slide gate plates in the system (right) and a slide gate system in operation (bottom left).

2: Principle of a slide gate system – left side open position and right side closed position

The material properties of the slide gate assemblies achieved by use of CTPht in the manufacturing process, guarantee the observance of the required safety standards in dealing with liquid steel. This is because the service life of slide gate plates is a limiting factor for performance of the slide gate system. The lifetime of slide gate systems depends on factors such as refractory material, plant operating conditions and steel grades. Therefore, the chemical composition (refractory material) of slide gate components is a key to ensure process and workers safety and consequently extended service life of the slide gate systems and thus higher productivity and improved economical operation.

2 Manufacture of slide gate assemblies

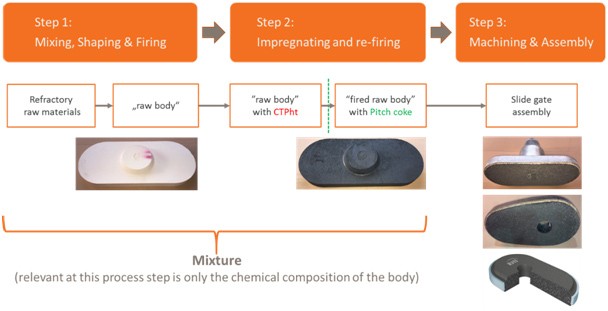

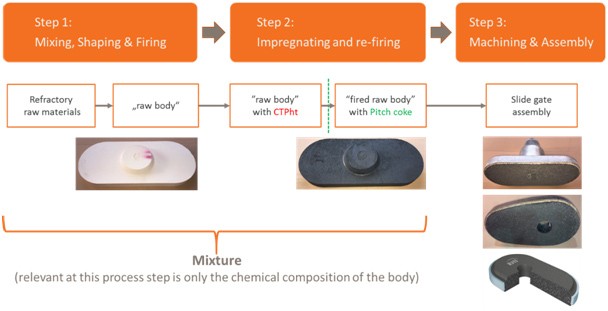

Figure 3 provides an overview on the production of slide gate assemblies the different intermediate products and the use of CTPht:

Figure 3: Production of slide gate assemblies

2.1 Step 1: Mixing and forming of raw materials

In the first production step, a primary product – the so called “raw body” – is produced by mixing, forming and firing of different raw materials (e.g. Magnesia, Aluminium oxide, Graphite, Resin and Pitch). At this stage, no CTPht is used. The resulting “raw body” has a porous structure and provides the cavities/pores, which are then filled with CTPht in the following step.

It is important to mention that the shape and surface of the “raw body” differs significantly from the shape/surface/design of the final slide gate assemblies. The forming performed at this stage does not provide the required final shape, surface and design of produced slide gate assemblies. The final shape, surface and design is obtained by machining in the final production step (see Section 2.3). For the overall manufacturing process, the machining step is mandatory since slide gate assemblies with a shape/surface/design similar to the “raw bodies” in practice are useless for the final application. The chemical composition of the “raw body” however is a prerequisite for the subsequent production steps and the performance of the final slide gate assembly. In other words, the chemical composition of the “raw body” is important for the next production step (and the final product) in contrast its shape/surface/design.

Consequently, the resulting so called “raw body” does not fulfil the article definition under REACH[1](according to Article 3(2) of REACH an article is defined as an ”object which during production is given a special shape, surface or design which determines its function to a greater degree than does its chemical composition”). The product resulting from step 1 consequently is a substance (reaction mass) under REACH.

2.2 Step 2: Impregnating and firing

In the second production step, impregnation of the “raw body” with CTPht – filling of the pores/cavities of the “raw body” with CTPht – is performed. During the subsequent firing process, CTPht is completely transformed into “Pitch Coke”. The substance CTPht serves as the meltable (requirement for impregnation) parent substance (precursor) for the transformation product of the chemical reaction –“Pitch Coke”. The new substance “Pitch Coke” is formed via the chemical reactions of poly-condensation and polymerization during the firing step (high temperature). “Pitch Coke” (CAS 140203-12-9) is exempt from registration and authorisation under REACH, Annex V[2]

During step 2 only the chemical composition of the “raw body” is changed, but not the surface, shape and design. Similar to step 1, the shape, surface and design of the resulting object is secondary, as the “fired raw body” does not fulfil any other function besides use for further processing (shaping). Of crucial importance is the chemical composition (complete transformation of CTPht) of the object that allows the subsequent production of the final products by shaping.

“Pitch coke” leads to a high mechanical strength and a high slag resistance of the final slide gate assemblies. The slide gate system is crucial to process safety and safety at work in the casting of liquid steel in the steel making process. A failure of a slide gate will cause an uncontrolled release of hot liquid steel with dangerous consequences for workers and the environment. There are no other means for getting this required high mechanical strength, and slag resistance by applying other substances (e.g. bitumen, resin). The chemical composition, especially the content of “Pitch coke” in slide gate assemblies, is crucial for the functioning of the final products and an important safety element in the steel making process.

2.3 Step 3: Machining

After the transformation from CTPht to “Pitch coke”, the object undergoes different machining steps (e.g. grinding, cutting etc.) to achieve the final shape, surface and will finally be fitted with a metal band, metal can/cassette or metal sheet to achieve the final design.

3 Evaluation of legal situation

According to REACH, an intermediate is defined as “a substance that is manufactured for and consumed in or used for chemical processing in order to be transformed into another substance”. In the guidance document on intermediates – Appendix 4: Definition of intermediates as agreed by Commission, Member States and ECHA on 4 May 2010 – it is pointed out: “The status of a substance as an intermediate is in fact not specific to its chemical nature but to how it is used following manufacturing”.

It is clear that during the manufacture of slide gate assemblies, CTPht is converted into “Pitch coke” at industrial sites. Consequently, there are two main points to consider when evaluating whether the use of CTPht in the refractory industry is an intermediate use:

- Substances used for the production of articles cannot be regarded as intermediates as according to Article 3(15), a substance is only considered as intermediate if it functions as a starting material for the manufacture of another substance.

- As soon as the main aim of the chemical process is not to transform a substance into another substance, or when a substance is not used for this main aim but to achieve another function, the substance used for this activity should not be regarded as an intermediate under REACH. An example is the use of acrylamide in acrylamide-based grouting agents. Here, acrylamide is used in the manufacture of another substance during which it is itself transformed into that other substance, namely a polymer. However, the acrylamide is not used for the purposes of undergoing synthesis, as defined in Article 3(15) of Regulation No 1907/2006. It is not used with the aim of manufacturing that other substance, the main purpose of the chemical process being to obtain a sealing function that occurs when the acrylamide grouting agent polymerises. The use of acrylamide as a grouting agent is therefore not considered to be an intermediate use, but rather an end use of the substance.

Regarding point a), as explained above, the “raw body” and the “fired raw body” cannot be regarded as articles under REACH as due to the shape (surface and design) of these preliminary products no other use than further processing is possible (end use in the steel industry is impossible). The next processing step 3 does not require any specific shape (surface and design) of the intermediate products from the previous steps. The product achieved after step 2, namely the “fired raw body” is a mixture consisting of the reaction mass achieved in step 1 and “Pitch coke” synthesized from CTPht in step 2. It is irrelevant that the “fired raw body” has a specific form, as at this stage only the composition of the “fired raw body” is of interest. This mixture (“fired raw body”) is subsequently used in step 3 to produce an article, namely the slide gate assembly. At this stage, CTPht is not present anymore and therefore CTPht as such is not used in the manufacture of the article itself (as for example curing agents in case of articles made from polymers or substances used for surface treatment of articles). The “fired raw body” undergoes different machining steps like grinding and cutting to achieve the final shape, surface and is finally fitted with a metal band, metal can/cassette or metal sheet to achieve the final design. After this step, one may conclude that the design of the object is of similar importance as the composition, as this final step results in the properties (shape and surface) required for proper and safe functioning of the slide gate assembly. The precise shape and the defined surface property besides the chemical composition guarantee process safety and safety at work in the casting of liquid steel in the steel making process.

When looking at point b) it is obvious that a use of a substance is not regarded as an intermediate use in case the main purpose of the chemical process is not the manufacture of a new substance but another effect like sealing function resulting from polymerization reactions or change of surface properties of articles. In general, the properties of every article are a result of the chemical composition and the “Pitch coke” being part of the composition of the slide gate assemblies in combination with the other components gives the article specific properties like high mechanical strength and a high slag resistance.

However, in the slide gate assemblies manufacturing process CTPht has no other function than being transferred to “Pitch coke”. CTPht is neither used with the intention to close/seal the pores of the “raw body” (like in the case of acrylamide mentioned above) nor is the product of the chemical reaction transferring CTPht into “Pitch coke” (the “fired raw body”) an article as such and the chemical reaction does also not aim at changing the surface properties of the “raw body” (or an article).

Against this background, it is clear that the main aim of the chemical process (step 2) is to produce a mixture consisting of the reaction mass produced in step 1 and “Pitch coke” which is subsequently used in step 3 to manufacture articles. There is no other function and the chemical reaction is not an integrated part of producing articles.

There is a clear difference between the manufacturing process of slide gate assemblies and CTPht impregnated refractory bricks. In contrast to the manufacture of slide gate assemblies, there is no machining step (step 3) after the chemical transformation of CTPht to “Pitch coke” during manufacture of refractory bricks. Already before impregnation with CTPht and firing, the shape, surface and design of the refractory brick is developed. The “raw body” in this case consequently already constitutes an article and the use of CTPht aims at changing the (surface) properties of this article (increase resistance). In this case, the use of CTPht is an integrated part of the production of an article (impregnated refractory brick) as the chemical transformation of CTPht is the last manufacturing step of the article comparable to surface treatment and therefore part of the manufacture of the article and not the production of a substance subsequently used to manufacture an article.

In other words, in contrast to the manufacture of impregnated refractory bricks, in the present case the aim of the chemical transformation of CTPht is the manufacture the new substance “Pitch coke”. This new substance “Pitch coke” (in a mixture with other substances gained from step 1) is subsequently used to manufacture articles (slide gate assemblies) by machining in production step 3.

According to the relevant sections of the REACH regulation[3], Art. 3(15), Art. 2(1c), Art. 2(8b) and the applicable ECHA guidance documents[4] [5], the substance CTPht when used in the manufacture of slide gate assemblies is an intermediate under REACH and therefore exempted from authorisation.

[1] According to Article 3(15), a substance is only considered as an intermediate if it functions as a starting material for the manufacture of another substance – substances used for the production of articles can therefore not be regarded as intermediates.

[2] ECHA guidance for Annex V: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/13632/annex_v_en.pdf

[3] REACH regulation: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02006R1907-20140822

[4] ECHA – Guidance on intermediates: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/13632/intermediates_en.pdf

[5] ECHA – Guidance on articles: http://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/13632/articles_en.pdf

Se ha tratado de un curso en el que se ha combinado a la perfección las clases teóricas con el laboratorio y las visitas a empresas relacionadas con el sector.

Se ha tratado de un curso en el que se ha combinado a la perfección las clases teóricas con el laboratorio y las visitas a empresas relacionadas con el sector.

The tiered approach to free allowance allocation for the EU ETS carbon leakage list is a concept which undermines the aim of the EU ETS and contradicts the October 2014 European Council Conclusions. It would not ensure the delivery of cost-effective greenhouse gas emission reductions, but on the contrary would have a deleterious impact on the wider European economy and would result in an increase in global emissions. A tiered approach would result in an inadequate level of carbon leakage protection for all ceramic sectors. Among others, we urge that the following key points are taken into account:

The tiered approach to free allowance allocation for the EU ETS carbon leakage list is a concept which undermines the aim of the EU ETS and contradicts the October 2014 European Council Conclusions. It would not ensure the delivery of cost-effective greenhouse gas emission reductions, but on the contrary would have a deleterious impact on the wider European economy and would result in an increase in global emissions. A tiered approach would result in an inadequate level of carbon leakage protection for all ceramic sectors. Among others, we urge that the following key points are taken into account: